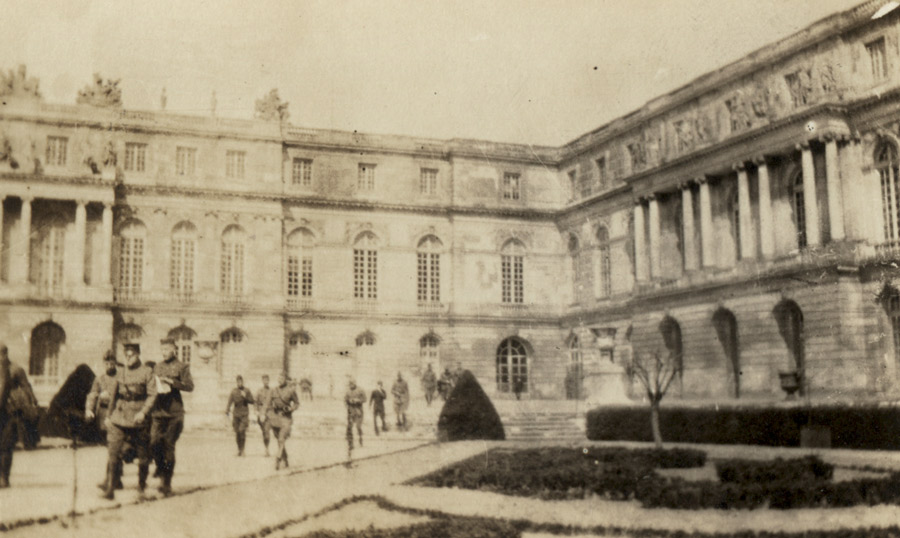

Formally opened on January 18, 1919, the Paris Peace Conference was the international meeting that established the terms of peace after World War I. Peacemaking occurred in several stages, with the Council of Four, also known as the “Big Four”—Prime Ministers Lloyd George of Great Britain, Georges Clemenceau of France, Vittorio Orlando of Italy and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson—acting as the primary decision-makers for the first six months, and their foreign ministers and ambassadors overseeing the remainder of the conference.

By the time the Allies formalized peace with the former Central Powers through a series of treaties, including an additional negotiation with the new nation of Turkey in 1923, the fragmented process of “making peace” had lasted longer than the war.

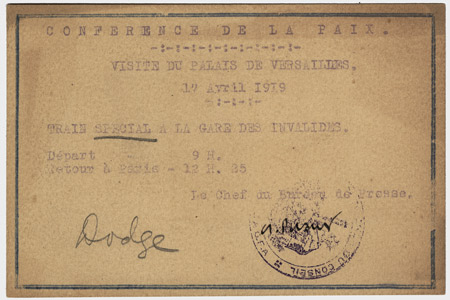

a stamped seal. It is signed " width="450" height="300" />

a stamped seal. It is signed " width="450" height="300" />

Allied leaders faced a difficult task, far greater than the only comparative peace conference in 1815 that officially ended the Napoleonic Wars. Four empires—Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire—lay shattered, their people facing an uncertain future amid social and political unrest. There were also calls for new states based on Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self‑determination.

“… one thing is clear: as Wilson arrived in France in December, 1918, he ignited great hopes throughout the world with his stirring Fourteen Points – especially the groundbreaking concept of ‘self-determination.’ Yet, Wilson … seemed vague as to what his own phrase actually meant.”

— Diplomat Richard Holbrooke, writing in the foreword of Margaret MacMillian’s book, Paris 1919.

No clear explanation of “self-determination” was ever provided by Woodrow Wilson. Many inspirationally perceived it to mean an identified grouping of people should have the liberty to create the government it would like. Deep conflict occurs upon implementation when determinations must be made on what identifies a “grouping of people” and what rights are provided with “liberty.”

Those in Paris not only had to determine the articles of peace for the former Central Powers but also faced countless demands from people throughout the Middle East, Africa and Asia. They also needed to consider the demands of their own countries, who, in the case of Great Britain and France specifically, sought physical and material compensation for the losses they suffered during four years of war.

Black and white photograph of the Versailles palace Hall of Mirrors filled with a large crowd surrounding a table of seated dignitaries." width="900" height="584" />

Black and white photograph of the Versailles palace Hall of Mirrors filled with a large crowd surrounding a table of seated dignitaries." width="900" height="584" />

Though certainly not perfect, the settlements they reached were nonetheless an earnest attempt at bringing lasting peace to a world wracked by war and, in the context of the period, offered hope for a better world than that which existed prior to 1914.