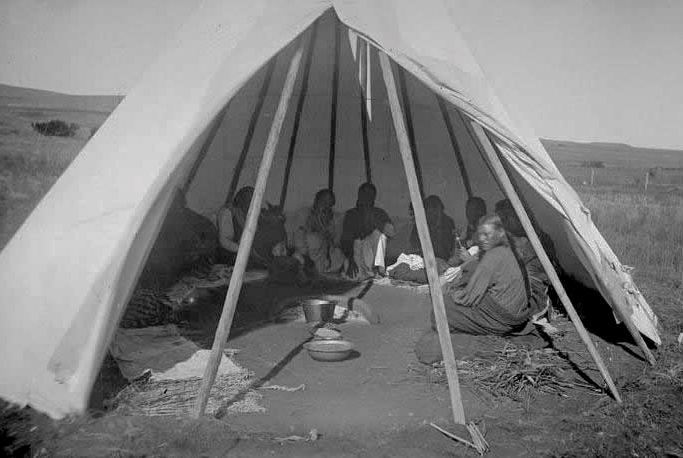

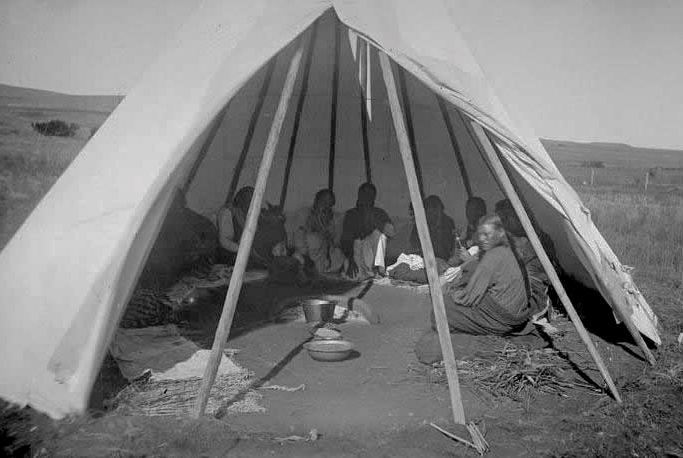

The 1994 amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 allowed Native Americans to use peyote in religious services. This peyote ceremony was photographed in 1892. (Image via the Forest Service of the United States Department of Agriculture, public domain)

The 1994 amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 provided that “the use, possession, or transportation of peyote by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremonial purposes in connection with the practice of a traditional Indian religion is lawful, and shall not be prohibited by the United States or by any State.”

It went on to allow governments to enforce specific prohibitions against ingesting such drugs by on-duty law enforcement officials and members of the military. Congress adopted the law after the Supreme Court issued decisions that failed to protect sacramental drug use.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 had provided that “it shall be the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions of the American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut, and Native Hawaiians, including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonial and traditional rites.”

Native Americans constitute a small percentage of the population, so Congress passed this legislation, in its view, to protect minority religious beliefs.

According to Louis Fisher (2001/2002), the 1978 law expressed “only a general policy” and lacked enforcement mechanisms.

He observes, for example, that lower federal courts did not consider the statute to require blocking the construction of dams that would flood Native American holy sites.

Moreover, the Supreme Court ruled in Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1988) that the free exercise clause did not require the government to prevent logging in a National Park near sacred Indian grounds.

In Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), the Court ruled that a state was not compelled to exempt the sacramental use of peyote by Native Americans because the drug laws in question were general laws, not ones aimed at particular religious adherents.

Citing its power under section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce equal protection, Congress responded to the Smith decision by adopting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993. It sought to require courts to apply a compelling interest test before justifying restrictions on religious exercise.

A year after adopting RFRA, Congress moved to provide specific protection for the sacramental use of peyote by Native Americans by amending the American Religious Freedom Act of 1978.

In City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), however, the Court ruled that instead of enforcing the Constitution, in enacting the RFRA, Congress had unconstitutionally sought to change its application to the states. Congress responded by adopting a more limited law, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000, which applied specifically to federal property. Conflicts and accommodations are likely to continue in this area in the near future.

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.